Some day I believe honest historians (both of them) will conclude that Trump’s administration was the most consequential and effective one-term presidency in American history, whose legacy will last for a long time. The best comparison would be Lincoln, who never got to serve his second term. Most one-term incumbents who are defeated lose because they have been abject failures, which Trump most assuredly wasn’t (which is why, unlike all past defeated incumbents who lost votes, Trump got 10 million more than his initial election).

Trump may or may not purposely dominate the political scene in the background as Teddy Roosevelt did from 1909 – 1912 and then run again in 2024, but I argue that Trumpism will dominate the scene for a long time to come, and that any successful GOP presidential nominee will need to be a Trumpist. I go further, in fact, and believe the shuffling of the issue map and the realignment of voting coalitions are as substantial as FDR and the New Deal—and it took FDR four terms to effect that change.

This series will explain where and why, and will culminate with an article offering a wider field theory of Trump that I argue still escapes even many sympathetic Trump observers.

Let’s start today with just the single issue of China (or “Chy-nah,” as Trump likes to enunciate it). I was struck by some recent survey findings from Pew Research displayed in the chart below. You can see that public opinion toward China has turned sharply negative all around the world over the last few years. Trump did that. And it will leave a residue that Biden will have to deal with. Biden—and craven corporate America that doesn’t want to see its lucrative Chinese market shrink—may try to go back to business as usual. But it will come at a political cost. Trump forever shattered the complacency of the China-accommodationists of both parties over the last 20 years.

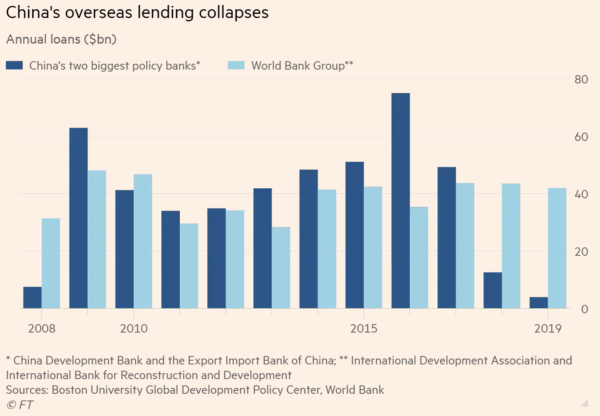

And even though Trump’s actual policies toward China were a mixed bag, there are clear signs he rattled the Chinese leadership, and contributed to some of the internal tensions and problems facing the Chinese system. The Financial Times over the weekend notes some significant changes in China’s international lending practices. China’s government control banks were lending massively (more than the World Bank and its affiliates in many years) to promote their “belt and road” strategy that aimed to secure markets for China. But this was the epitome of predatory lending. When a developing country was unable to make payments on loans, China would convert the debt into equity, and thus extend their ownership of foreign infrastructure. You might even call this imperialism. In any case, as this chart shows, China’s lending has suddenly dried up.

Notice: All comments are subject to moderation. Our comments are intended to be a forum for civil discourse bearing on the subject under discussion. Commenters who stray beyond the bounds of civility or employ what we deem gratuitous vulgarity in a comment — including, but not limited to, “s***,” “f***,” “a*******,” or one of their many variants — will be banned without further notice in the sole discretion of the site moderator.