One of the many odd things about the New York Times‘s “1619 Project” on slavery is that Martin Luther King Jr is barely mentioned (ditto Frederick Douglass). This omission may not be accidental, since both Douglass and King found sources for the remedy of slavery inside the American founding that today’s left wishes to repudiate completely. It will be a curious thing to see whether and how the 1619 Project appears in any of today’s observances of MLK’s birthday (or whether, in the fullness of time, there will be a push to rename MLK Day for someone or something else).

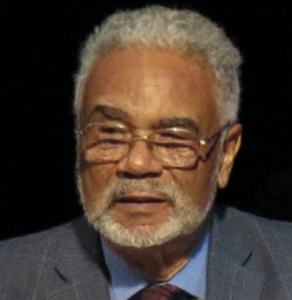

Clayborne Carson

The most unexpected thing to come out of the 1619 Project is that the most vigorous attack on it has come from the left, specifically the World Socialists, who have featured several prominent American historians shredding the project. We’ve mentioned some of this before, but the World Socialist Web Site just now has a new interview up with Clayborne Carson, a black historian at Stanford who is the director of Stanford’s Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute. Carson was chosen by Coretta Scott King to oversee the publication of The Papers of Martin Luther King. Carson was also one of the principal historical advisers for the PBS series about the civil rights movement, “Eyes on the Prize.”

If you read the entire interview it is clear Carson is very liberal, but also retains the same perspective of King and Douglass about how to think about the American Founding, and its indispensable role in making slavery a central political problem for the first time in human history. Although he is measured in his criticism, it is clear Carson doesn’t think much of the premises of the 1619 Project.

Here are some highlights from the long interview:

Q: I’d like to ask you something that we’ve been asking all the historians with whom we’ve been speaking. And that is whether or not you were approached by the authors of the 1619 Project as it was being prepared or prior to its publication?

Carson: No, no I wasn’t, which is strange because if you go to our website, we have a lot of educational materials for schools. So, I wasn’t approached as a historian, but I’m also an educator engaged in on-line teaching, trying, as much as possible, to get free material in the hands of students. I would have loved to work with theNew York Times, with all of their clout and resources, to make a change in terms of how American history is taught in the schools.

I just think that part of the problem of this whole project is that they did not really approach this as a collaborative activity involving historians, educators, and journalists. It seems quite obvious that the number of people involved in the actual process was quite limited.

Q: It also seems that it was written to a preconceived determination, and that historians who might have a somewhat different take were avoided. It’s also not clear to whom they did speak. The editor-in-chief, Jake Silverstein, in his reply to the five historians, said that they spoke to a group of African American scholars, but they didn’t say who was in that group.

Carson: Yes, and that was a little bit strange. You know if I were called in to have a meeting at theNew York Timesand they told me they’d like to do this project to make people more aware of the deep roots of African American history within American history and the importance of 1619, I would have said fine, that sounds wonderful, how can I help? I can understand, however, why some scholars would be reluctant because of the work that should go into something like this. I was very much involved in Eyes on the Prize, for example.

Q: Right, you were the senior academic advisor for Eyes on the Prize?

Carson: I was one of four. That was a three-year commitment. We met regularly for three years to produce that series. There was a lot of research, the selection of whom to interview. We had what we called “the school” and at every stage the filmmakers would come in with footage, and we would critique it: “Well, why didn’t you interview this person? Why didn’t you ask that question?” It was an interactive process for three years to get that on the air. On 1619, I’m just not sure on a lot of the factual background of this, and maybe you’re trying to figure that out, too. . .

A lot of their focus seems to be the founding of the United States as a nation. The way I would look at that, is that at that time, for a variety of reasons, you have a predominant group, white men, beginning to articulate a human rights ideal. We can study why that happened when it happened. It had to do with the Enlightenment, the spread of literacy, the rise of working class movements. All of these factors led people to start talking in terms of human rights. It was both an intellectual movement from the top down and a freedom struggle from the bottom up. People begin to speak in terms of rights: that, I, we, have rights that other people should respect. The emergence of that is important.

And it does affect African Americans. We know that from Benjamin Banneker and lot of other black people who realized that white people were talking about rights and said, ‘well we have rights too.’ That’s an important development in history, and an approach to history that doesn’t say we should privilege only the rights talk of white people. There’s always a dialogue between that and oppressed people. You have to tell the story from the top down, that intellectuals began to articulate the notion of rights. But simultaneously, non-elites are doing that—working class people, black people, colonized people. . .

Q: I think one of the things that is missing in the lead essay by Nikole Hannah-Jones is any appreciation of the power of the contradiction that was introduced in 1776 with the proclamation of human equality, and also the impact of the Revolution itself. I thought in our interview with Gordon Wood he took that question up very effectively, pointing out that slavery became very conspicuous as a result of the Revolution. Also disregarded is the Afro-Caribbean historian Eric Williams, who analyzed the impact of the American Revolution on the demise of slavery. Instead the Revolution is presented as a conspiracy to perpetuate slavery.

Carson: Yes, and it’s wonderful to concentrate on that contradiction because that to me explains Frederick Douglass, it explains King. What all of these people were united on was to expose that contradiction—and we should always keep exposing it—the contradiction between the self-image of the United States as a free and democratic country and the reality that it’s not. If you are a black leader, your job is to expose that contradiction. If you go through a list of all the great orations in African American history, nearly all of them focus on that. They want to expose that and use that contradiction.

Q: I’m glad you mentioned Douglass and King. Richard Carwardine, in our interview with him, said that he was struck by the absence of Douglass, whose name does not appear in the lead essay or anywhere else. The same is true of King, whose name appears only once in a photo caption. The Civil Rights movement is barely mentioned. Black Power and Malcolm X are absent. The list of what’s left out is astonishing—no A. Phillip Randolph, no Harlem Renaissance. But I wanted to ask you about the absence of King, and any significant attention to the civil rights movement, and what you make of that. . .

Carson: I think that’s the saddest part of this, that the response of the New York Times is simply to defend their project. Rather than to say, we welcome the critique, let’s work with you to see what we can do. Obviously, this would have been better done a year ago, two years ago, but it’s never too late. And particularly if the purpose of this is to have an impact on the way young people are educated. I’m very concerned about that.

Stay tuned for this week’s Power Line podcast, which will be up this afternoon. I’ll be taking up the subject of MLK Day with “Lucretia” and a special guest.

Notice: All comments are subject to moderation. Our comments are intended to be a forum for civil discourse bearing on the subject under discussion. Commenters who stray beyond the bounds of civility or employ what we deem gratuitous vulgarity in a comment — including, but not limited to, “s***,” “f***,” “a*******,” or one of their many variants — will be banned without further notice in the sole discretion of the site moderator.