I’ve been meaning for a while to knock out an article on the theme, “there’s nothing wrong with America that 4 percent growth won’t solve.” That’s an exaggeration, of course, but not much of one. Faster economic growth will alleviate a number of our leading problems, especially stagnant wages, a sinking labor force participation rate, badly unbalanced budgets, adult children living in basements, ESPN’s sinking ratings, etc.

One difficulty is that one of our major parties is completely uninterested in revving up economic growth. Unlike the Democratic party of John F. Kennedy, which held an explicit doctrine called “growth liberalism,” embraced the idea that “a rising tide lifts all boats,” and campaigned on the theme of “let’s get the country moving again” (sounds a little but like someone’s current campaign slogan, no?), today’s liberals care not for growth, but are obsessed with redistribution and what James Piereson rightly labeled “punitive liberalism.” (Another historical irony is that the liberals of the Kennedy era were scornful of Eisenhower because they thought economic growth in the 1950s was too slow; now liberals like Paul Krugman look back at the 1950s as a golden era for the middle class, and especially for union power.) An administration that was serious about economic growth would at the very least approve the Keystone pipeline, and fast-track every possible construction project in the country, instead of embracing policies that make energy more expensive and clog up labor markets (just for starters).

I’m agnostic about whether income tax cuts will juice economic growth in the same fashion as the 1980s, though our corporate tax system badly needs to be reformed and would likely have some measurable positive benefit. I’ve received a thorough briefing of the Tax Foundation’s economic model—the one they’ve used to score each of the candidates’ economic plans and which the media have referenced in questions in the debates—and its essentially a cost-of-capital model whose largest growth and income effects come not from tax rate changes but the tax treatment of business investment, which has been flagging badly of late.

A much bigger factor is likely the huge revival of heavy government regulation, like Dodd-Frank, the new overtimes rules, and the pending “Clean Power Plan” that essentially nationalizes the nation’s electric utility industry. There’s been a lot of talk about “regulatory uncertainty” in the Obama era, as we wait to see the full effects of the burdens of Obamacare and other mandates. Today the Wall Street Journal has a major article on Dodd-Frank that makes for sober reading. It provides an extraordinary look at just how out of control Obama-era regulation has become:

The 2010 Dodd-Frank law, passed in the wake of the financial crisis and designed to prevent another, is one of the most complex pieces of legislation ever. At more than 22,200 pages of rules, it is equivalent to roughly 15 copies of “War and Peace” and covers matters from how much capital banks must set aside to how they can advertise.

Those rules and others have spawned a regulatory apparatus that is the fastest-growing component of the financial sector, with banks hiring tens of thousands of new staff whose job is to keep their employers right with the new regime. Federal agencies have dispatched thousands of their own minders to set watch at banks.

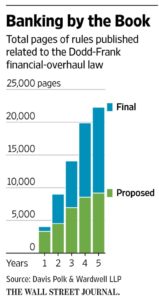

One of the more striking aspects of this story is displayed in the nearby chart, which shows that final rules issued by the regulators ended up being twice as long as proposed rules. Among these are lots of regulations that have nothing whatever to do with any of the causes of the financial crisis of 2008, such as new regulations of ATM fees and checking overdraft fees—regulations which very few members of Congress thought they were voting for when they passed Dodd-Frank. Clearly a lot of the regulations are from the wish lists of consumer groups and other leftist activists.

One of the more striking aspects of this story is displayed in the nearby chart, which shows that final rules issued by the regulators ended up being twice as long as proposed rules. Among these are lots of regulations that have nothing whatever to do with any of the causes of the financial crisis of 2008, such as new regulations of ATM fees and checking overdraft fees—regulations which very few members of Congress thought they were voting for when they passed Dodd-Frank. Clearly a lot of the regulations are from the wish lists of consumer groups and other leftist activists.

Does anyone think all of these compliance employees are adding to economic growth? The WSJ reports:

Banks pulled back from financing areas ranging from student lending to certain types of mortgages. They no longer make bets with their own money, known as proprietary trading, and have collectively ceased working with hundreds of thousands of individual or company accounts.

The heightened regulatory environment led 46% of banks to pare back their offerings for loan accounts, deposit accounts or other services, according to an American Bankers Association survey of compliance officers last year.

What is all this costing?

The six largest U.S. banks by assets in 2013 together spent at least $70.2 billion that year on regulatory compliance, up from $34.7 billion in 2007, according to the most recent study by policy-analysis firm Federal Financial Analytics Inc., which said costs have continued to mount since then.

Does anyone think a $70 billion price tag passes any sensible cost-benefit test? What effect is that having on the formation of new banks or bank mergers that might be beneficial? You could simply pass a tax on the large banks asking for half of this amount to be put in a special reserve fund to bail out banks (which we’ll do anyway when Dodd-Frank inevitably fails to prevent another financial meltdown) and free up capital for more productive use. Alternately, you could dispense will all of this detailed micromanagement of the banks with one very simple regulation: require much higher reserve capital—maybe as high as 25 or 30 percent—and then simply sit back and watch banks watch their own risks more prudently, or get taken over when in distress by other banks. (Big banks simply hate this idea, which is what makes me think it might be good.)

This is just the finance sector. I’ll be back later with further thoughts on new labor regulations that are surely depressing job growth.

Notice: All comments are subject to moderation. Our comments are intended to be a forum for civil discourse bearing on the subject under discussion. Commenters who stray beyond the bounds of civility or employ what we deem gratuitous vulgarity in a comment — including, but not limited to, “s***,” “f***,” “a*******,” or one of their many variants — will be banned without further notice in the sole discretion of the site moderator.